Revolution in AR

It’s Time for a Revolution in Academic Resourcing

This new academic year is unlike any other. Colleges and universities are coping with nasty deficits and cash flow problems, but the probable long-term disruptions are even more worrisome. Never in my half-century of close involvement with academic resourcing have I seen such threats to the operating and financial sustainability of so many institutions. As Charles Dickens said, it is the worst of times.

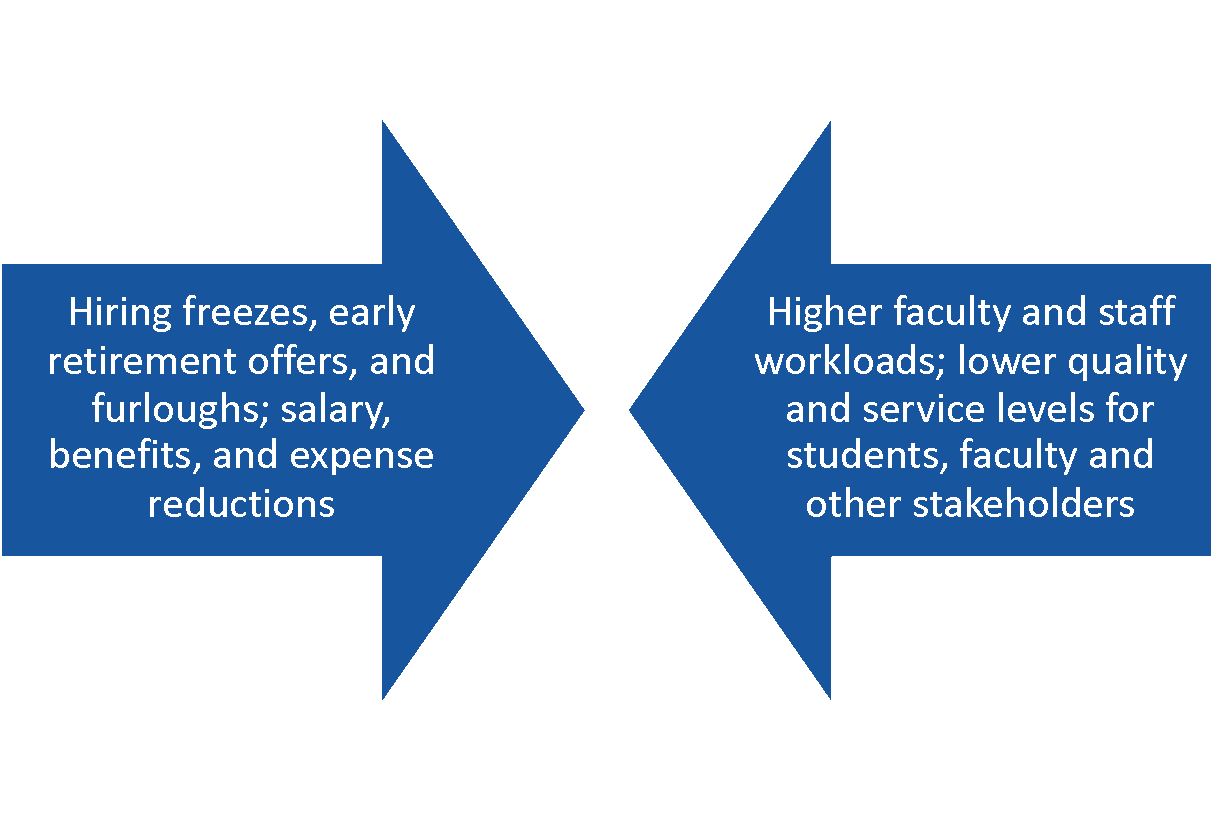

Typical first responses are to freeze faculty and staff hiring, offer incentives for early retirement and furlough employees where necessary, freeze or even reduce salaries and benefits, and slash expense budgets. These actions can staunch the immediate financial hemorrhage,

but at the cost of increased workloads and reduced quality and service. The picture says it all: the cuts and speedups force out dollars by squeezing people. While this may be necessary, the damage must be repaired if the institution is to remain viable once the pandemic is over. Recent conversations suggest that schools know they need address this problem. But how?

Recent advances in concepts, data and tools, together with the manifest need and disruptive enablement of the COVID crisis, can make these the best of times for effecting the needed changes. Perhaps some of the academy’s long-festering problems will get solved along the way. As noted in previous blogs and elsewhere, I’ve been pushing hard on these advances and working with Gray Associates to reduce them to practice. This Blog presents an overview of our current thinking. Future ones will describe the key tools in more detail. I believe that an academic resourcing revolution is in the offing and that it’s badly needed.

A Roadmap for Restoring Sustainability

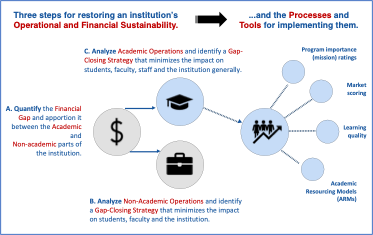

The steps, processes, and tools needed to restore operational and financial sustainability in the wake of COVID, and indeed at any other time, are called out in the following diagram. The academic elements are highlighted because they are the subject of this blog series.

- Institutions should begin by quantifying the financial gap and making a preliminary judgment about how it should be apportioned between the academic and non-academic parts of the institution. Long-run financial equilibrium is a key objective. This means the budget is balanced and that there are no hidden liabilities: for example, no unfunded financial obligations, deferred maintenance or spending rates that eat into the real value of endowments. For more on this and related subjects see chapter 5 of my Reengineering the University.

- Next comes an analysis of the institution’s non-academic operations and development of a strategy for closing their share of the financial gap. There’s no substitute for clear-eyed judgments about service levels (e.g., in student services and human resources) and spending on compliance with policies and regulations, and also the productivity of the people and systems involved. None of this is easy, but the tasks differ little from the productivity-boosting actions of business firms. It’s important to be rigorous here, both for intrinsic reasons and because faculty need to understand that everything possible is being done in the non-academic areas.

- Last and of course not least, comes work with the institution’s academic operations: specifically, teaching and, where applicable, research. This is what I call academic resourcing, and where I believe a revolution is in the offing.

Course and Program Portfolios

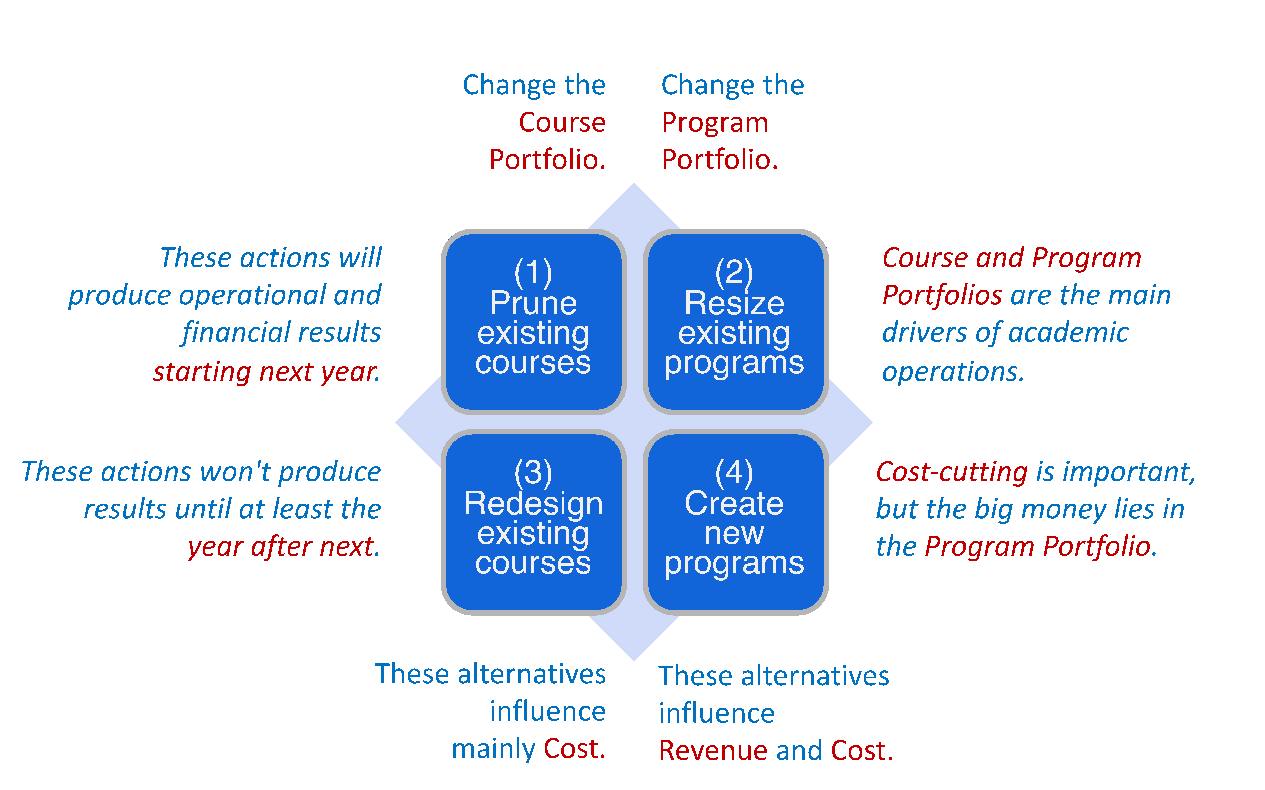

What’s new here is: (1) an understanding that institutions should actively manage their course and program portfolios and do so in holistic terms; and (2) that they have or can acquire the data and tools needed for holistic management. (Research portfolios also may need such management, but that’s beyond our scope here.) As noted earlier, the objective is to make the institution’s teaching-related tasks financially sustainable and consistent with reasonable workloads while minimizing unintended negative consequences for mission contribution and educational quality.

The above doesn’t mean centralized management, but rather that the provost and deans promulgate what might be called “indicative strategies” for nudging departments and faculty in desired directions. The diagram below presents the four domains in which these strategies can be developed. It updates the version presented in my June blog on money problems to reflect our recent work, but it follows the same general logic. We believe the four-fold depiction exhausts the possibilities for strategy development, but of course new ideas will be welcome.

Course and program portfolios are the main drivers of academic operation. While course-based cost-cutting is important, the big money lies in the resizing of program portfolios and the creation of new programs. Gray now has a predictive model for gauging the incremental revenue, cost, and margin of any proposed set of program enrollment changes—taking each course’s range of acceptable class sizes and the effects of course overlap among programs into account. This opens the way for evidence-based holistic portfolio analysis.

Even more exciting is our algorithm for informing conversations about what the set of program enrollment changes should be. The algorithm works off the aforementioned predictive model. It brings in market scores and judgments about program importance (contribution to mission), and it can use results from a Gray program evaluation workshop if one has been conducted. Tests of the model show there can be substantial mission, market, and margin improvements even when the resizing holds total student numbers constant. Greater improvements will occur when total enrollment is allowed to increase, and even greater ones when new programs are added to the mix. Stay tuned for more on this, and also for discussions about how to gauge program importance and bring student success into the policy analysis.

“Needed: Real Solutions”

Why colleges and universities have been slow to attack the economics of education has been a concern for many years. My research suggests that, although deans, chairs and faculty are the only people who can manage portfolios without undermining academic values and quality, they are trained in their disciplines and lack the tools, management background and cultural perspective to do so. This may have been acceptable in the past, but tradition and momentum cannot be relied upon in the post-COVID environment. What’s needed is an “all-hands-on-deck” approach that uses every tool and person available for analyzing the academic and economic implications of novel curricular designs, teaching modes, and program enrollment profiles.

There is real danger that, in their scramble to cope with COVID’s immediate fallout, provosts, deans, program heads, department chairs, and financial officers will ignore what may be a unique opportunity to master the economics of their educational processes—and thus settle for non-solutions that leave their institutions in an unsustainable condition. To quote Dickens once again, we need “a season of light rather than darkness, a spring of hope rather than a winter of despair.” Will this be “epoch of belief and wisdom” or will we look back on COVID as an “era of incredulity and foolishness”?

Published at Tue, 22 Sep 2020 17:17:53 +0000